Services

Areas of Expertise

Mr Stevenson is able to support patients with a variety of common conditions, a list of the most common are below including details of treatment and diagnosis.

Below are the most common areas of expertise Mr Stevenson is asked to consult on.

Anal Fissure

- An anal fissure is a visible tear in the lining of the anal canal, extending from the skin on the outside of the anus inwards. It affects approximately one in every 300 people, occurring equally between men and women, predominantly in the 15–40 age group.

- Classic symptoms include sharp anal pain and bright red bleeding during bowel movements.

- Some may experience mucus discharge, while others may be asymptomatic.

- Incidental discovery during examinations for other anal issues is possible.

- Poor blood supply to the anal area, combined with potential anal muscle spasm, contributes to fissure formation.

- Debate exists over specific causes; hard stool passage is suggested but not confirmed.

- Anal fissures can be associated with medical conditions such as pregnancy, childbirth, inflammatory bowel disease, and sexually transmitted diseases.

- Medical: a. Conservative measures can alleviate symptoms during the healing process. b. Stool softeners can aid in reducing pain during bowel movements. c. Diltiazem cream, applied externally and internally, may help relax anal muscles and enhance blood supply for healing.

- Surgical: a. Considered if conservative or medical interventions fail. b. Botulinum toxin injection into the anal sphincter aims to relax muscles and enhance blood supply. c.Surgical options include rectal advancement flap or lateral anal sphincterotomy to promote healing. d. Success rates vary, with lateral anal sphincterotomy having a higher success rate compared to rectal advancement flap.

- Typically diagnosed in outpatient settings through visual examination.

- Examination under anaesthetic (EUA) can be an option if necessary.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful for complex cases.

- Anal fissures are common and can vary in symptoms.

- Conservative, medical, and surgical treatments are available based on the severity and persistence of symptoms.

- Individualized treatment plans are crucial, considering factors like duration, symptoms, and potential complications.

- Surgical interventions aim to address muscle spasm, blood supply issues, and enhance healing while minimising the risk of incontinence.

Anal Fistula

Anal Fistulas: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Definition:

- An anal fistula is an abnormal tunnel that runs from the outside skin in the anal area, through the anal muscles, and opens onto the inside lining of the anus.

- Overall, one person in 10,000 will develop an anal fistula, with a higher prevalence in the 20–40 age group and a male predominance.

Causes:

- Anorectal Abscess:

a.About one-third of people develop a fistula after an anorectal abscess.

b.Infection of an anal gland leads to an abscess formation, and if it discharges in two directions (through the skin and anus), an anal fistula is formed. - Crohn’s Disease and Cancer:

a.Anal fistulas can also be caused by inflammatory conditions like Crohn’s disease.

b.More serious conditions such as cancer can contribute to the development of anal fistulas.

Symptoms:

- Recurring pain and associated discharge.

- Itching around the anal area.

- Recurring infections around the anus, similar to anorectal abscess symptoms.

Diagnosis:

- Visual examination in the outpatient department is common.

- Redness around the area, induced discharge upon pressing, and identification of the internal opening may occur.

- Examination under anesthesia (EUA) can be performed if necessary.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for complex cases; definitive diagnosis may sometimes require EUA.

Surgical Treatment:

- Treatment is essential for ongoing problems; however, some minor fistulas may be left untreated.

- Surgical options depend on the complexity of the fistula.

Fistulotomy:

- Opens the length of the fistula to the skin surface, allowing slow wound healing.

- Typically performed for low fistulas with minimal muscle involvement.

Seton Placement:

- A suture introduced into the fistula, allowing drainage from the inside out.

- Preferred for high fistulas with significant muscle involvement.

- Seton may be left permanently or cause the fistula to move to a more manageable position.

Surgical Fistula Repair (Advancement Flap):

- A more complex operation aiming to close the internal opening and preserve anal sphincter muscles.

- Options include anal mucosa or anal skin advancement flap, fibrin glue injection, fistula plug, or LIFT procedure.

- Treatment in patients with weak anal muscles is approached cautiously due to potential impacts on bowel continence.

- In cases of high fistulas, discussions between the surgeon and patient involve weighing the benefits of surgery against the risk of incontinence.

Conclusion:

- Anal fistulas, while rare, can cause recurring symptoms and complications.

- Early diagnosis through outpatient examinations and appropriate surgical intervention tailored to the specific fistula type is crucial.

- Surgical options aim to promote healing while minimising the risk of incontinence, and the choice of treatment depends on the individual characteristics of the fistula.

Anismus

Anismus (Pelvic Floor Hypertonicity): Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Definition:

- Anismus, also known as pelvic floor hypertonicity, is a condition where the external anal sphincter and the puborectalis muscle contract instead of relaxing during a bowel movement.

- The puborectalis muscle, a core pelvic floor muscle, normally forms a sling around the lower part of the rectum, but in anismus, it remains tense and contracted.

Symptoms:

- Sensation of blockage or resistance during attempted bowel movements.

- Painful bowel movements leading to obstructive constipation.

- Problems like faecal impaction (hard, dry stools in the rectum) and megarectum (enlargement of the rectum diameter).

- Straining during bowel movements, further irritating pelvic floor muscles.

- Some individuals may need to apply manual pressure inside the anus to facilitate bowel movements.

Causes:

- The exact cause of anismus is not well understood.

- Individuals with anismus often experience difficulty relaxing the puborectalis muscle during a bowel movement.

Diagnosis:

- Clinical examination of the rectum.

- Additional tests, including anorectal physiology and proctography, may be conducted.

Treatment:

- Pelvic Floor Retraining:

a. Many patients report symptom improvement through exercises that help the sphincter muscles relax during bowel movements. - Botulinum Toxin Injection:

a. Botulinum toxin injection into the puborectalis muscle is an alternative treatment.

b.The first injection aids in diagnosis and if anismus is confirmed, a beneficial effect may be observed within the first week (up to six weeks).

c.If the initial injection is successful, a repeat injection is given for long-term benefits, potentially lasting for years or being permanent.

d.If the first injection is unsuccessful, an underlying internal rectal prolapse may be suspected, leading to further examination under anesthetic in the operating theatre.

Conclusion:

- Anismus, or pelvic floor hypertonicity, is characterized by the abnormal contraction of pelvic floor muscles during bowel movements.

- Symptoms include difficulty passing stool, pain, and complications like faecal impaction.

- Diagnosis involves clinical examination and additional tests.

- Treatment options include pelvic floor retraining exercises and Botulinum toxin injections, with the latter showing success in providing long-term relief for some individuals. If unsuccessful, further investigation for internal rectal prolapse may be necessary.

Anorectal Abscess

Anorectal (Perianal) Abscess: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Definition:

- An anorectal abscess is a collection of pus near the anus, often leading to hospital admissions globally.

- Commonly affects individuals aged 20–30, with a higher incidence in men.

Anatomy:

- The anal canal is surrounded by the anal sphincter, composed of two sets of circular muscles.

- Anal glands (anal crypts) situated between the muscles produce secretions that cross the inner muscle ring to enter the anus.

Causes:

- 90% of anorectal infections result from abscess formation in anal glands.

- The remaining 10% may be caused by conditions like Crohn’s disease, hidradenitis suppurativa, trauma, or occasionally cancer.

Symptoms:

- Pain around the anus, often throbbing or dull.

- Increased pain while sitting.

- Discharge or swelling in the painful area.

- Possible fever.

- Pain intensity increases until the abscess spontaneously discharges or is surgically treated.

Diagnosis:

- Clinical examination by a specialist.

- Imaging studies like CT or MRI may be required for deep-seated infections or rarer causes.

- Examination under general anesthetic in the operating theatre may occasionally be needed for diagnosis and simultaneous treatment.

Treatment:

- Early Stage:

a. Antibiotics alone may suffice if caught early and managed by a GP.

b. If pain and signs worsen, urgent referral to a specialist is necessary. - Surgical Intervention:

a. Abscess incision and drainage is the primary surgical treatment.

b. The wound is left open for gradual healing from the inside out.

c. Antibiotics are rarely needed post-surgery unless specific conditions (e.g., diabetes) or severe inflammation are present.

Prognosis:

- Two-thirds of individuals will not experience recurrence after surgery.

- The remaining third may face further issues, including the development of new abscesses or fistula formation (abnormal connection between the anus and skin), requiring additional surgical intervention.

Colorectal Cancer

Bowel (Colorectal) Cancer: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Overview:

- Bowel cancer includes colon cancer (large intestine) and rectal cancer (final part of the large intestine).

- Typically arises from a benign growth called a polyp, with genetic changes leading to uncontrolled growth and cancer formation.

- In the UK, bowel cancer is the third most common cancer, with around 41,000 diagnoses annually. Lifetime risk is 1 in 16.

Risk Factors:

- Alcohol consumption, smoking, obesity, high saturated fat intake, family history of colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, presence of polyps, and age over 60 are considered risk factors.

Bowel Screening Program:

- Initiated in 2006 across mainland UK to detect polyps and precancerous changes, allowing early intervention before symptoms appear.

Symptoms:

- In early stages, bowel cancer may be asymptomatic.

- Possible symptoms include blood in faeces, change in bowel habits, unintentional weight loss, fatigue, and abdominal pain.

Diagnosis:

- Based on symptoms, medical history, and diagnostic procedures (colonoscopy or CT colonography).

- A multidisciplinary hospital team discusses all colorectal cancer cases.

Treatment:

- Surgery:

a. Colectomy: Removal of the affected segment of the large bowel.

b. Low Anterior Resection: Common for rectal cancer where anal sphincter muscles are not affected.

c. Extra-levator Abdominoperineal Resection (eLAPE): For rectal cancer involving anal sphincter muscles, requiring removal of the anus and a permanent colostomy. - Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy:

a. Used to shrink the tumour before potentially curative surgery.

b. Administered based on the tumour’s location, size, type, and spread. - After Surgery:

a. Roughly half of patients can be cured by surgery alone.

b. If chemotherapy is needed post-surgery, referral to a medical oncologist is made.

Prognosis:

- More than 90% of bowel cancers can be treated successfully if diagnosed early.

- The specific treatment plan depends on the cancer’s characteristics, and patients are guided through the process by a colorectal surgeon, medical oncologist, or other specialists as needed.

Constipation

Understanding Chronic Constipation: Causes, Classification, and Seeking Medical Advice

Overview:

- Constipation is common and can result from dietary changes, travel, or habitual factors.

- A healthy lifestyle with a balanced diet, sufficient fluids, and exercise usually prevents constipation.

- Chronic constipation can be complex, affecting 10 – 12% of the population.

- Chronic constipation may lead to symptoms like abdominal bloating, passing wind, and abdominal pain.

Chronic Constipation Classification:

- Functional (Primary) or Secondary:

a. Functional: A condition on its own, classified into normal-transit, slow-transit, and outlet constipation.

b. Secondary: Results from an underlying condition or medication use. - Normal-Transit Constipation:

a. Colonic motility is normal, but patients may have trouble emptying bowels due to factors like harder stools. - Slow-Transit Constipation:

a. Abnormal functioning of the enteric nervous system (ENS) leads to slower passage of stool through the colon.

b. Medical therapy is the primary approach, but surgery (subtotal colectomy) is considered in some cases. - Outlet Constipation:

a. Pelvic floor dysfunction, often due to pelvic floor muscle failure to relax during evacuation.

b. Conditions include internal rectal prolapse, rectocoele, and pelvic floor prolapse.

c. Treatment may involve Botulinum toxin injection, pelvic floor physiotherapy, laxatives, or surgery.

Secondary Chronic Constipation Causes:

- Medication:

a. Various medications, including painkillers, diuretics, antidepressants, and antispasmodics, can contribute to constipation. - Underlying Conditions:

a. Medical conditions like hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, diabetes, coeliac disease, and neurological disorders may lead to chronic constipation.

b. Anorectal problems such as anal fissure, anismus, and pelvic floor prolapse can also contribute.

Importance of Medical Consultation:

- Chronic constipation, when unrelated to benign causes, can result from underlying conditions.

- It’s crucial to seek medical advice, especially if there are changes in bowel habits, persistent constipation, or symptoms like abdominal pain.

- Exclusion of serious causes, such as colorectal cancer or diverticular disease, is essential through examinations like colonoscopy.

Conclusion: Chronic constipation, while not typically leading to severe consequences like cancer, can have a significant impact on the quality of life. Understanding its underlying causes, classification, and seeking medical attention for a proper diagnosis and management are vital for individuals experiencing persistent constipation.

Crohn's Disease

Understanding Crohn’s Disease: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Overview:

- Definition: Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

- Symptoms: Abdominal pain, diarrhoea, blood in stools, complications in the back passage, anal fissures, anorectal fistulas, skin tags, and bowel incontinence.

- Complications: Bowel narrowing (stenosis), infections, malabsorption, weight loss, and potential effects on other organs (eye, liver, joints, skin, blood clot risk).

- Onset: Adolescence/young adulthood with a potential second spike later in life.

Causes and Risk Factors:

- Genetic Component: Over 30 genes linked to CD; 30 times higher risk if a sibling has CD.

- Environmental Factors: More prevalent in industrialised countries; associated with diet (animal protein vs. vegetable protein), smoking increases severity.

Diagnosis:

- Challenges: CD diagnosis can be challenging due to mild symptoms and overlap with other conditions.

Diagnostic Tools:

- Colonoscopy: Visualising upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts.

- Capsule Endoscopy: Camera swallowing for imaging the entire gastrointestinal tract.

- Magnetic Resonance Enterography: Imaging small bowel.

- Blood Tests: Detecting inflammation and malabsorption.

- Faecal Calprotectin Test: Differentiating between CD and irritable bowel syndrome.

- Incidental Discovery: CD may be discovered during unrelated surgeries.

Treatment:

- No Cure: CD is chronic, and there is no cure; management aims for symptom control and maintaining a good quality of life.

Diet:

- No Specific Foods: No specific foods proven to cause CD, but certain items can aggravate symptoms.

- Dietary Management: Limiting dairy, low-fat foods, smaller, more frequent meals, and adjusting dietary fibre based on individual response.

Medication:

- Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Mesalazine for mild symptoms.

- Immunosuppressants: Azathioprine for immune system suppression.

- Steroids: Needed during flare-ups.

- Antibiotics: Metronidazole or ciprofloxacin for infections around the anus.

- Localized Medications: Suppositories or enemas for CD affecting the last part of the colon.

- Intravenous Steroids: For severe flare-ups.

Surgery:

- Goal: Preserve as much bowel as possible.

- Common Operations: Removal of a segment of the small bowel; colectomy if the colon is affected.

- Total Colectomy: Last resort, removal of the entire large bowel.

- Recurrence: CD can return after surgery; repeated surgeries may be necessary.

Conclusion: Understanding Crohn’s disease involves recognising its chronic nature, diverse symptoms, and the need for a personalised approach to diagnosis and management. While there is currently no cure, ongoing research aims to unravel its complex genetic and environmental factors, providing hope for improved treatment strategies in the future. Medical, dietary, and surgical interventions play crucial roles in alleviating symptoms and preserving patients’ quality of life.

Diverticular Disease

Understanding Diverticular Disease: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Overview:

- Definition: Diverticular disease involves the development of small outpouchings (diverticula) in the bowel wall, with common occurrences in the sigmoid colon.

- Prevalence: Increases with age; present in approximately half of people in their fifties and three-quarters in their late seventies. Associated with constipation, low-fibre diet, and genetic factors.

- Symptoms: Often asymptomatic; symptoms can include bloating, abdominal discomfort, and changes in bowel habits (diarrhoea or constipation). Diverticulitis, marked by inflammation or infection of specific diverticula, can lead to more severe symptoms, including fever and abnormal blood tests.

Diagnosis:

- Incidental Discovery: Often found during large bowel investigations (colonoscopy or CT colonography).

Diagnostic Tools:

- Colonoscopy or CT Colonography: Commonly used for diagnosis.

- CT Scan: Necessary for diagnosing diverticulitis.

- Challenges: Similar symptoms to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can make differentiation challenging. Surgery might be recommended to rule out bowel cancer.

Treatment:

- Symptom Management: Treatment depends on symptoms; IBS-type symptoms associated with diverticular disease are managed similarly to IBS.

- Dietary Intervention: Fibre and fluid intake improvement may slow the progression of diverticula.

- Emergency Admissions: Required for severe cases of diverticulitis with abscess formation or bowel perforation; drainage and antibiotics are common treatments.

- Surgical Intervention:

Elective Surgery: Considered for complications like colovesical or colovaginal fistulas and bowel strictures.

Partial Colectomy: Emergency surgery for perforated bowel wall.

- Limitations: Once diverticula form, they are permanent, and surgery does not eliminate them; dietary changes and symptom management are crucial.

Conclusion: Diverticular disease, characterized by the presence of diverticula in the bowel wall, is a common condition often associated with aging, constipation, and dietary factors. While many individuals remain asymptomatic, others may experience symptoms similar to irritable bowel syndrome. Diverticulitis, marked by inflammation or infection of diverticula, can lead to more severe complications requiring emergency or elective surgery. Diagnosis involves imaging studies, and treatment focuses on symptom management, dietary interventions, and, in severe cases, surgical procedures. Understanding the complexities of diverticular disease aids in providing effective care and improving patients’ quality of life.

Faecal Incontinence

Understanding Faecal Incontinence:

Faecal incontinence is the inability to control bowel movements, affecting various aspects of life. The condition results from a complex interaction involving the nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, pelvic floor muscles and emotions.

Types of Faecal Incontinence:

There are two main types: “urge” incontinence, where there’s a sudden need to reach a toilet, and “passive” incontinence, where individuals are unaware of the need to go.

Prevalence:

More common than perceived, with 6% of women under 40 and over 15% of older women affected. Surprisingly, 10% of men of any age experience faecal incontinence, with a higher risk as people age.

Causes:

Faecal incontinence is a symptom with multiple causes, categorized into groups like trauma, neurological conditions, constipation, cognitive issues, and diarrhoea related to certain conditions.

Diagnosis:

Seeking a colorectal surgeon is crucial. Examinations and tests like anal ultrasound, anorectal physiology, and defecating proctogram help identify potential causes.

Treatment Options:

- Conservative and Medical:

a. Dietary changes and medical interventions to improve stool consistency. b. Pelvic floor physiotherapy and biofeedback.

c. Colonic and rectal irrigation for some individuals.

d. Specialized treatments for those with irritable bowel syndrome.

Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation:

a. Non-invasive therapy involving acupuncture-type needles.

Surgery:

Considered a last resort, surgical options include repairing a damaged anal sphincter, rectal prolapse repair, sacral nerve stimulation, and anal bulking.

Holistic Approach:

Faecal incontinence requires a holistic approach, considering the intricate interplay between muscles, nerves, cognition, and stool consistency. Tailoring treatment to individual needs is essential.

Haemorrhoids

Understanding Haemorrhoids:

The anus contains blood vessels and sphincter muscles, forming haemorrhoid tissue. When these vascular cushions become enlarged, they are known as haemorrhoids or “piles,” often described as the “varicose veins of the anus.”

Prevalence and Causes:

Haemorrhoids are common, affecting nine out of ten people, with symptoms usually arising between ages 40-60. While diet, fluid intake, and constipation play a role, other factors such as genetics, weight, chronic cough, and pelvic floor issues contribute. Pregnant women are especially prone.

Symptoms:

Most individuals with haemorrhoids experience minimal or no symptoms. Symptoms may include bright red bleeding, mucus discharge, itching, and prolapse of internal haemorrhoids. Pain can occur if a blood clot forms, leading to a thrombosed haemorrhoid.

Diagnosis:

Physical examination, including visual inspection for external haemorrhoids and skin tags, is common. Internal haemorrhoids are diagnosed using a proctoscope for a detailed examination. Symptoms are not always indicative of haemorrhoids, and further tests may be conducted to rule out serious conditions like bowel cancer.

Treatment:

- Conservative:

a. Treatment is often unnecessary, and many people manage minor symptoms without intervention.

b. Dietary changes, increased fibre, reduced tea/coffee intake, and avoiding diarrhoea or constipation can help.

c. Haemorrhoids rarely lead to long-term problems or cancer. - Non-surgical:

a. Injection sclerotherapy or rubber band ligation in the clinic for internal haemorrhoids.

b.These procedures aim to reduce blood supply and alleviate symptoms. They are not suitable for external haemorrhoids. - Surgery:

a. Reserved for external and internal haemorrhoids not responding to non-surgical treatments.

b. Traditional haemorrhoidectomy for external haemorrhoids involves removing tissue.

c. For internal haemorrhoids, various procedures like Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation (HALO), transanal haemorrhoid dearterialisation (THD), rectoanal repair (RAR), and stapled haemorrhoidopexy are considered in the operating theatre.

Overall, surgical treatments are open procedures performed as needed for specific cases, while non-surgical options can effectively manage symptoms in many individuals. The choice of treatment depends on the type and severity of haemorrhoids.

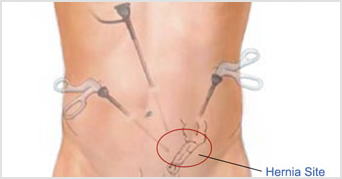

Understanding Abdominal Hernias:

A hernia occurs when there is a weakness in the abdominal wall, allowing organs to protrude through, forming a bulge. This weakness can be present from birth or develop over time. Factors like obesity, straining, persistent cough, and certain medical conditions increase the risk of hernias.

Types of Abdominal Hernias:

- Inguinal Hernia:

a. Common in the groin, more prevalent in men, occurring in about 25% of men and 3% of women.

b. More common in infants and men over 50. - Umbilical Hernia:

a. Near the navel, common in infants, especially premature babies.

b.Can persist into adulthood in some cases. - Femoral Hernia:

a. Rarer, mainly in women, accounting for 2% of hernias and 6% of groin hernias.

b. Risk increases with age, often confused with inguinal hernias. - Incisional Hernia:

a. Occurs through a previous abdominal surgery incision.

b. Risk factors include malnutrition, wound infection, diabetes, corticosteroid use, and emergency surgery.

Symptoms:

- Felt as a lump in the groin, around the navel, or at the site of previous abdominal surgery.

- May be asymptomatic, but pain can occur, especially during lifting.

- Size may change with activities like laughing, coughing, or going to the toilet.

Diagnosis:

- Clinical examination by a colorectal surgeon.

- CT scan or ultrasound may be used in challenging cases.

Treatment:

- Conservative:

a. Small, asymptomatic hernias can be monitored. b. Supportive measures with a custom-made corset (truss) for those at higher surgical risk. - Surgery:

a. Recommended for most adults as hernias rarely improve on their own and may worsen over time.

b. Risks of complications increase with age.

c. Open or laparoscopic approach based on hernia size and location.

d. Mesh is commonly used to reduce recurrence risk.

Risks and Considerations:

- If untreated, there is a risk of obstruction or strangulation, potentially requiring emergency surgery.

- Femoral hernias carry a higher risk of complications.

- Laparoscopic surgery may have a shorter recovery period.

- Recurrent hernias may be approached differently in terms of surgical technique.

Conclusion:

Surgery is typically recommended for abdominal hernias due to the risk of worsening symptoms and potential complications. The choice between open and laparoscopic surgery depends on hernia size and location, with mesh commonly used to enhance repair durability. Recurrent hernias may benefit from a different surgical approach.

Hernias

A hernia occurs when there is a weakness in the muscular abdominal wall that keeps the abdominal organs in place. This weak area allows organs and tissues to push through, or herniate, producing a bulge. The weakness may be present from birth or develop over a long period of time. Anything that increases the pressure in the abdomen can increase the risk of developing a hernia. Being overweight or obese, straining while moving or lifting heavy objects, having a persistent heavy cough, and having a history of multiple pregnancies are known risk factors for abdominal hernia. The risk of developing an abdominal hernia is increased in patients with certain medical conditions, such as emphysema, and those on dialysis for kidney disease.

The four types of abdominal hernia commonly seen in a colorectal clinic are:

Inguinal hernia – a hernia occurring in the groin and found more often in men than in women. Inguinal hernia occurs in about 25% of men but in only 3% of women. They are more common in infants and in men aged older than 50 years.

- Umbilical hernia – this type of hernia occurs near the navel (belly button) and is common in infants and young children, especially in babies born prematurely. In many cases, the hernia disappears and the abdominal muscles reseal in the first few months of life, but a minority of children need surgery. An umbilical hernia can also develop in adults, who may have had a weak area around the navel since birth.

Femoral hernia – a rarer type of hernia, occurring mainly in women and accounting for 2% of all hernias and 6% of all groin hernias. The risk of developing a femoral hernia increases with age, so most of these hernias are found in middle-aged or older women. They are thought to be more common in women because of their wider pelvis and a slightly larger femoral canal, into which intestinal tissue can herniate more easily than in men. Femoral hernias can be easily confused with inguinal hernias by both patients and doctors.

Incisional hernia – a hernia that occurs through a previously made surgical incision in the abdomen. They are thought to be caused by failure of a surgical wound to heal, but are probably the result of multiple patient and technical factors. An incisional hernia is most likely to appear at around 6 weeks after surgery, when people become more physically active. Advances in surgical technique and materials have not removed this problem. Overall, the risk of developing an incisional hernia is about 1%, but may be up to 20% in patients with malnutrition, wound infection or diabetes, if the patient has been on corticosteroids, or if surgery is being performed as an emergency.

Symptoms

An abdominal hernia is felt as a lump in the groin (inguinal and femoral hernias), around the navel (umbilical hernia), or at the site of previous abdominal surgery (incisional hernia). People with an abdominal hernia may have no symptoms whatsoever and their hernia may only be found on examination by a doctor for something else. Some people do get pain from their hernia, especially when lifting. The hernia may appear to get bigger when laughing, coughing, or going to the toilet, and then shrink when the person is relaxing or lying down. Symptoms vary during the day. If the person has a strenuous job, any straining may increase the size of the hernia. The early small hernias seem to cause more symptoms. These symptoms may then diminish or go away altogether as the hernia gets slightly bigger, only to reappear when the hernia becomes even larger.

Diagnosis

An experienced colorectal surgeon can readily diagnose an abdominal hernia by taking a detailed history and performing a clinical examination. The hernia usually presents as a lump under the skin, which may only be present on standing up and disappear on lying down. Occasionally an abdominal hernia may be producing typical symptoms but be harder to find. In these cases, a CT scan or ultrasound may be useful.

Treatment

Conservative

If a hernia is small and causing no symptoms, it can be left safely alone initially. However, hernias don’t go away of their own accord. Over time, hernias tend to get bigger as the abdominal wall gets weaker and more tissue bulges through. Still, many people are able to delay surgery for months or even years.

Some people have additional medical problems that increase the risks associated with surgery to the point that these risks are greater than the risk of leaving the hernia alone. The treatment recommended for these patients is usually a custom-made corset (truss) to provide support for the hernia.

Surgery

Surgery is recommended for most adults with an abdominal hernia as the hernia is unlikely to get better by itself and will almost certainly get worse over time. Further, the risk of complications increases with age. Any patient with increasing symptoms from a hernia, a hernia that is increasing in size and/or not getting smaller when lying down, or that is interfering with work performance or activities of everyday living should consider a surgical hernia repair.

If a hernia is not surgically repaired, there is a small but ever-present risk of the portion of bowel in the hernia becoming stuck (obstructed), causing intense pain and needing emergency surgery. There is also a risk of the portion of bowel lodged in the hernia losing its blood supply (becoming strangulated). A strangulated hernia is potentially fatal and requires emergency surgery within hours to release the trapped tissue and restore its blood supply. Emergency surgery in these circumstances may also require the affected part of the bowel to be removed.

The risks of obstruction and strangulation are much higher for femoral hernias, even small ones, than for the more common inguinal and umbilical hernias. If a femoral hernia is suspected (or cannot be excluded), an appointment with a colorectal surgeon should be made as soon as possible. Unfortunately, over half of patients with a femoral hernia still arrive in hospital as an emergency, with all the increased risks that entails.

Inguinal hernia repair, umbilical hernia repair, and femoral hernia repair can be performed by an open approach or a laparoscopic approach. Small and medium-sized hernias, especially if they are on both sides of the body, are usually best suited for a laparoscopic approach. Laparoscopic surgery is said to have a shorter recovery period. Larger hernias and hernias that are not reducing are often repaired by an open approach. The general recommendation is to use mesh for hernia repair as it markedly reduces the chances of the hernia coming back.

Open surgery and laparoscopic surgery are excellent procedures, but both have a 1% chance of the hernia returning. If a hernia recurs after a previous repair, the new repair may be best done using a different approach to that done previously. For example, if the previous hernia surgery that failed was an open repair, then laparoscopic surgery should be considered and vice versa. Laparoscopic surgery should probably not be performed in patients who have had major abdominal surgery before.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Understanding Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS):

Definition:

- IBS is a collection of symptoms, including abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhoea, and constipation, collectively diagnosed based on these symptoms.

- It is a common condition, affecting up to one in four people, with various subtypes: IBS-C (constipation-predominant), IBS-D (diarrhoea-predominant), and IBS-A (alternating diarrhoea and constipation).

Possible Causes and Triggers:

- Gastroenteritis and Trauma:

a. IBS may be triggered by gastroenteritis or traumatic life events.

b. Research indicates that damage caused by gastroenteritis can lead to increased permeability of the gut membrane, potentially causing inflammation. - Psychological Factors:

a. While stress is often associated with IBS, reducing stress may not necessarily improve symptoms.

b. Certain psychological traits may be linked to conditions predisposing individuals to IBS. - Malabsorption and Bile Salts:

a. One-third of people with diarrhoea-predominant IBS may have malabsorption of bile salts, causing irritation and diarrhoea. - Bacterial Overgrowth:

a. Bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel can lead to inflammation and IBS-like symptoms.

b. Decreased numbers of normal bacteria in the gut may allow harmful bacteria to increase, contributing to symptoms.

Heterogeneous Nature of IBS:

- IBS may not have a single cause but rather be an umbrella term for various conditions.

- Some individuals experience IBS temporarily or with minor symptoms, while others face ongoing challenges, sometimes alongside other severe conditions.

Management:

- No specific test can diagnose IBS, and symptoms overlap with other serious bowel conditions.

- Any change in bowel habits should prompt a visit to a colorectal specialist to rule out other potential causes.

- Comprehensive management requires an understanding of both pelvic pain and IBS.

- IBS triggers, such as certain foods, antibiotics, acute gastrointestinal illness, and stressful events, may act as the “final straw” in individuals predisposed to IBS.

Conclusion:

- IBS is a complex condition with diverse triggers and causes.

- Management involves excluding other serious conditions, understanding the individual’s unique situation, and addressing symptoms comprehensively.

- The multidimensional nature of IBS requires collaboration between medical professionals to provide effective care.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Understanding Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Organ Prolapse:

Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Function:

- The pelvic floor comprises muscles, fascia, ligaments, and tendons that support pelvic organs (bladder, uterus in women, and rectum) and assist in controlling bowel and urinary functions.

- Proper pelvic floor function involves a balance of strength, flexibility, and coordination.

Causes of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction:

- Childbirth and Age:

a.Women, especially after childbirth, are more prone to pelvic floor dysfunction.

b. Muscle mass decrease starts around age 40, accelerating after menopause, leading to potential dysfunction. - Genetic Factors:

a.Genetic components influence pelvic floor health, with some individuals having more elastic connective tissues.

b. Conditions like hypermobility syndrome, marked by weak connective tissues, can contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction.

- Constipation and Straining:

a. Chronic constipation and straining during bowel movements increase the risk of pelvic organ prolapse. - Pelvic Organ Prolapse:

a. Weakening, damage, or lack of coordination in pelvic floor structures may lead to pelvic organ prolapse.

b. Common types include rectal, vaginal, and small intestine prolapse.

Rectal Prolapse:

- External Rectal Prolapse: a. May cause difficulty in controlling bowel movements, frequent urges, and a bulging sensation in the vagina.

b. Occurs when the rectum protrudes outside the anus.

- Internal Rectal Prolapse: a. Results in obstructive defecation syndrome with a sensation of bowel blockage.

b. May require manual pressure for bowel emptying.

Small Bowel Prolapse:

- In women, part of the small bowel may prolapse into the vagina (enterocele), causing pelvic pressure and a sense of blockage during bowel movements.

Surgical Options for Pelvic Organ Dysfunction:

- Transanal Rectocele Repair:

a. An open procedure via the anus to repair a rectocele, offering a lower-risk option with some chance of recurrence. - Rectoanal Repair:

a. An open procedure via the anus for rectocele or internal rectal prolapse, useful in managing residual symptoms after major robotic repair. - Delorme’s Procedure:

a. An open procedure via the anus to repair external rectal prolapse, generally reserved for less fit patients with short prolapses. - Perineal Rectosigmoidectomy (Altemeier’s Procedure): a. An open procedure via the perineum to repair external rectal prolapse, usually for less fit patients.

- Ventral Mesh Rectopexy and Variants (e.g., Sacrocolporectopexy):

a. Laparoscopic or robotic procedures via the lower abdomen, suitable for various pelvic organ dysfunctions, including rectocele, enterocoele, internal rectal prolapse, external rectal prolapse, or vaginal prolapse.

Considerations for Surgery:

- Choice of procedure depends on factors like the cause of prolapse, age, family plans, and overall health.

- Thorough discussions with healthcare providers help determine the most suitable repair approach.

Conclusion:

- Pelvic floor dysfunction and organ prolapse are complex conditions influenced by various factors.

- Surgical interventions offer tailored solutions based on the specific type and cause of the dysfunction.

- Comprehensive discussions with healthcare professionals assist individuals in making informed decisions about the most suitable treatment.

Pelvic Pain

Understanding Chronic Pelvic Pain (CPP):

Definition and Characteristics:

- CPP is pain in the pelvic area persisting for more than three months, occurring below the navel and between the hips.

- It can be acute or chronic, intermittent or constant, and may be associated with various underlying conditions or exist as a disorder on its own.

Common Causes of CPP:

- Neuropathic Pain:

a. Characterized by burning, tingling, shooting, or stabbing pain due to nerve damage or entrapment syndromes. - Endometriosis:

a. Tissue similar to uterine lining grows in pelvic structures, causing moderate to severe pain in affected areas like ovaries, bowel, bladder, or pelvic lining. - Levator Ani Syndrome:

a. Musculoskeletal pelvic floor pain with trigger points and pressure areas, leading to aching or pressure sensations, aggravated by sitting and relieved by walking. - Proctalgia Fugax:

a. Rare condition involving recurrent episodes of sudden, sharp shooting pain around the anus, extending into the pelvis and abdomen.

Diagnosis:

- Symptoms guide diagnosis; detailed information helps identify the cause.

- Considerations include pain duration, nature, aggravating or relieving factors, menstrual cycle or intercourse relation, and any past injuries, illnesses, or surgeries.

Examination and Investigations:

- Pelvic floor examination assesses muscle coordination, trigger points, and sensory changes.

- Laparoscopy may be performed to exclude endometriosis.

- Additional investigations may be required based on individual symptoms.

Treatment Approach:

- Treatment focuses on identifying and addressing the underlying cause of CPP.

Specific Causes and Treatments:

- Neuropathic Pain:

a. Collaboration with chronic pain physicians.

b. Medications targeting neuropathic pain. - Endometriosis:

a. Gynaecological consultation for moderate to severe cases.

b. Colorectal specialist referral for mild endometriosis to explore other causes before gynaecological procedures. - Levator Ani Syndrome:

a. Treatments include pelvic floor physiotherapy, medications (Amitriptyline, Pregabalin or Gabapentin), and Botulinum toxin injections into pelvic floor muscles.

b. Collaboration with a chronic pain physician for comprehensive management. - Proctalgia Fugax:

a. Management jointly by a colorectal surgeon and a chronic pain specialist. b.Treatment options for more severe cases.

Challenges in CPP Treatment:

- CPP is often associated with coexisting conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, connective tissue disorders, or mental health problems.

- Overlapping symptoms necessitate careful differentiation for effective treatment planning.

Conclusion:

- Chronic pelvic pain is a complex condition requiring a multidisciplinary approach.

- Tailored treatments aim to address the specific cause when identified or manage pain effectively when the cause is elusive.

- Colorectal specialists play a crucial role in diagnosing and treating CPP, especially when associated with bowel-related issues.

Pruritus Ani

Understanding Pruritus Ani:

Definition:

- Pruritus ani refers to itching in or around the anal area, impacting the quality of life for sufferers.

Epidemiology:

- Common in the age group of 40-60 years, with a higher prevalence in men (up to four times more likely than women).

- Occurs as either a minor, self-resolving condition or a severe, persistent issue.

Classification:

- Classified as secondary if associated with a lower bowel, anus, or skin condition; otherwise considered primary (idiopathic).

Underlying Causes:

- Skin Conditions: Eczema, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis can affect the anal area.

- Medical Conditions: Around 100 conditions have been linked to pruritus ani, including bowel cancer, haemorrhoids, anal fissures, weak anal sphincter, and internal rectal prolapse.

- Hygiene: In a small minority, poor hygiene contributes to pruritus ani.

Diagnosis:

- Determined through colonoscopy, examination under anaesthesia, and skin biopsy to identify potential underlying causes.

- Idiopathic cases should be approached with caution, as a missed underlying cause may be present.

Treatment:

- Eliminate Irritants:

a. Cease use of chemicals, including creams, soaps, and toilet paper.

b. Utilise water for cleansing; switch to hypoallergenic laundry products.

c. Dietary changes, eliminating potential triggers like coffee, tea, citrus fruit, etc. - General Control Measures:

a. Water-based creams and emollients for cleansing.

b. Petroleum ointment, Sudocrem®, or Cavilon® as a barrier after cleansing.

c. Aqueous cream and cotton wool balls for post-toilet cleansing outside the home.

d. Consider wearing gloves at night to prevent scratching. - Drug Therapy:

a. Hydrocortisone 1% ointment for mild to moderate symptoms without skin changes.

b. Stronger steroids for severe symptoms and skin changes for up to 8 weeks, followed by a switch to a weaker steroid.

c. Antifungal creams for fungal infections. - Anal Tattooing:

a. Reserved for cases unresponsive to other treatments and steroid-dependent individuals.

b. Performed under general anaesthesia using methylene blue to reduce sensation in the anal area.

c. Temporary relief lasting a few weeks; reduced sensation for up to a year.

d. Repeatable if necessary.

Conclusion:

- Pruritus ani is a complex condition with various potential causes.

- Thorough diagnosis, including identification of underlying conditions, is crucial for effective treatment.

- A multidisciplinary approach, involving lifestyle changes, hygiene practices, and medical interventions, is often necessary for symptom management.

- Specialised procedures like anal tattooing can be considered in specific cases where other treatments have failed.

Ulcerative Colitis

Understanding Ulcerative Colitis (UC):

Definition:

- Ulcerative Colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease affecting the colon and rectum, characterised by inflammation of the colon’s lining, resulting in reduced water absorption and bloody diarrhoea.

Aetiology:

- Combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- Familial predisposition observed, with an increased incidence in identical twins.

- Specific causes unknown, but stress and worry may trigger relapse or worsen symptoms.

Clinical Presentation:

- Diarrhoea, often bloody, due to impaired water absorption in the inflamed colon.

- Symptoms severity varies; patients with involvement limited to the last part of the large bowel may have milder symptoms.

- Approximately 15% of patients with initially mild UC may progress to more severe disease.

Complications:

- Association with an increased risk of bowel cancer, especially in cases of more extensive UC (pancolitis) with severe inflammation.

- Patients with extensive UC are offered annual screening colonoscopy for bowel cancer after eight years of active UC.

Diagnosis:

- Established through colonoscopy, a key diagnostic tool.

Treatment:

- Medication:

a. Anti-inflammatories, steroids, immunosuppressants, and newer biological therapies are utilised to reduce symptoms, induce remission, and prevent flare-ups.

b. Medication choices are tailored based on the severity of symptoms and individual patient needs.

c. Women with UC are advised to time pregnancies during remission periods. - Surgery:

a. Reserved for severe forms of UC associated with complications.

b. Total colectomy is a common procedure, often performed laparoscopically.

c. Emergency colectomy may result in an ileostomy (small bowel end brought out through the abdominal wall).

d. Elective colectomy offers options like ileostomy or ileal pouch surgery.

e. Ileal pouch surgery is considered for younger patients with good anal muscles, understanding the long-term nature and potential complications.

f. Surgical options and their implications discussed thoroughly with patients.

Conclusion:

- UC is a complex inflammatory bowel disease with varying degrees of severity.

- Management involves a combination of medications and, in severe cases, surgical interventions.

- Individualised treatment plans, considering the patient’s symptoms, disease extent, and preferences, are essential.

- Long-term monitoring and potential complications, including the risk of bowel cancer, are integral aspects of UC management.

Our Fees

At the Glasgow Surgical Clinic we believe private health-care fees should be transparent from the initial point of enquiry. Our fixed price packages cover the entire cost of the procedure (including the surgical, anaesthetic, pathology and hospital fees). All inpatient costs for accommodation and meals are also included. Patients with private medical insurance will be required to have the procedure pre-authorised by their insurers and if an excess applies this should also be paid directly to the hospital. Fixed price packages for some of the more commonly performed procedures are listed here. However, these prices are subject to change and it is advisable to check with the Business Office either at Ross Hall or the Nuffield before arranging your procedure.

-

Initial Consultation £200

-

Return Consultation £160

-

Flexible sigmoidoscopy £1,436

-

Colonoscopy (conscious sedation) £2,750

-

Colonoscopy (deep sleep sedation) £3,150

-

Upper GI endoscopy £2,000

-

Combined Upper GI endoscopy & colonoscopy (conscious sedation) £3,000

-

Combined Upper GI endoscopy & colonoscopy (deep sleep sedation) £3,500

-

Banding of Haemorrhoids £1,453

-

Inguinal (groin) Hernia Surgery £3,250

-

Umbilical Hernia £2,823

-

Pilonidal sinus surgery £3,026

-

Skin lesion removal (local anaesthetic) £1,100 - £1,710

-

Transanal haemorrhoid dearterialisation (THD) procedure £2,890

-

Haemorrhoidectomy £3,530

-

Excision of anal skin tags or abnormal skin around the anus £1,931

Our Approach

At the Glasgow Surgical Centre we pride ourselves on providing world-leading private medical expertise with our specialist surgeons combined with exceptional patient care. From your initial point of enquiry through to diagnosis and treatment, you’ll feel in safe hands throughout your entire consultation process.

The Glasgow Surgical Centre offers the very best in private surgical health care in Scotland.